‘One particularly puzzling aspect of academic and public dialogue about implicit prejudice research has been the dearth of attention paid to the finding that men usually do not exhibit implicit sexism while women do show pro-female implicit attitudes‘

Implicit bias tests have been an important tool in the armoury of Human Resources departments. The idea is that people have learned not to behave in an openly racist or sexist manner. However, they may still harbour prejudicial beliefs that could lead them to discriminate without being aware of it. These prejudices, that the subject may be unaware of, can be revealed by Implicit Association Tests (IATs), or so it is said.

The idea is that people are quicker to respond to associations they agree with than those they disagree with. For example, suppose someone was harbouring racist beliefs; when a positive word is associated with a black face, they are slower to respond (by button pressing) than when a negative association is presented. Broadly speaking, people are quicker to respond to associations they agree with and by doing so, they may reveal their underlying or implicit bias. It was assumed that people had learned not to display overt bias, but implicit biases were still rampant, particularly racial and sexist biases. On the basis of some pretty flimsy data sets, IATs were adopted by HR departments up and down the land. Putting aside the reliability of the data, the axis of bias being explored was largely racial. This was, after all, in the Black Lives Matter moral panic.

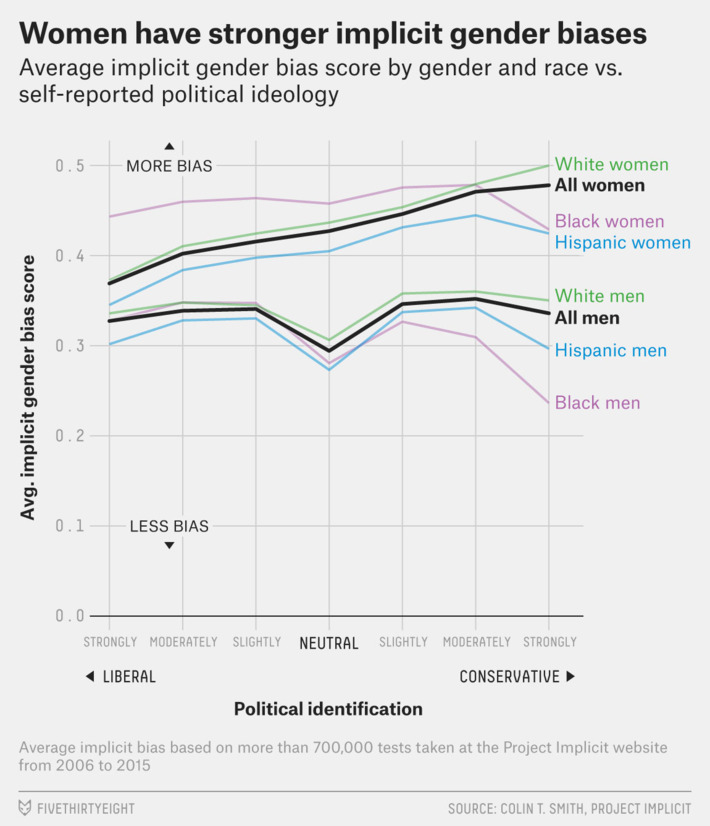

A few years ago, when the HR department at a place I used to work was presenting some of the data that was supposed to justify IATs, I noticed that women, across the board, seemed to be running higher levels of implicit bias. Something that was not mentioned or perhaps not even noticed by HR representatives (almost exclusively middle class, white and female). What surprised me even more was that when I asked them to go back a couple of slides and I pointed out this finding, my words were met with a stony silence and a suggestion that I was ‘missing the point’. The figure below is not from the HR presentation I viewed but shows similar albeit more comprehensive data.

The test-test reliability of IATs is low, so it would be wrong to point the finger at an individual on the basis of an IAT, but it may reveal something interesting about population-level differences. That is where things get interesting and that was where HR departments were and still are reluctant to tread.

The most comprehensive study using IATs to disclose group-level differences was published in 2023 in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 5,204 participants were assessed and rather than looking at a single dimension such as race this study examined multiple dimensions including race, age and sex. What they found contradicted most people’s expectations and, I suspect, the beliefs of most HR departments. The strongest bias was not on the basis of age or race. Instead, it was a pro-female or anti-male bias; a bias was found across all age and identity groups. The title of the paper says it all ‘Intersectional Implicit Bias: Evidence for Asymmetrically Compounding Bias and Target Gender‘ – that target gender was male.

The results of this study correlate with a wide range of other studies, some of which have been reviewed in previous posts here and here.

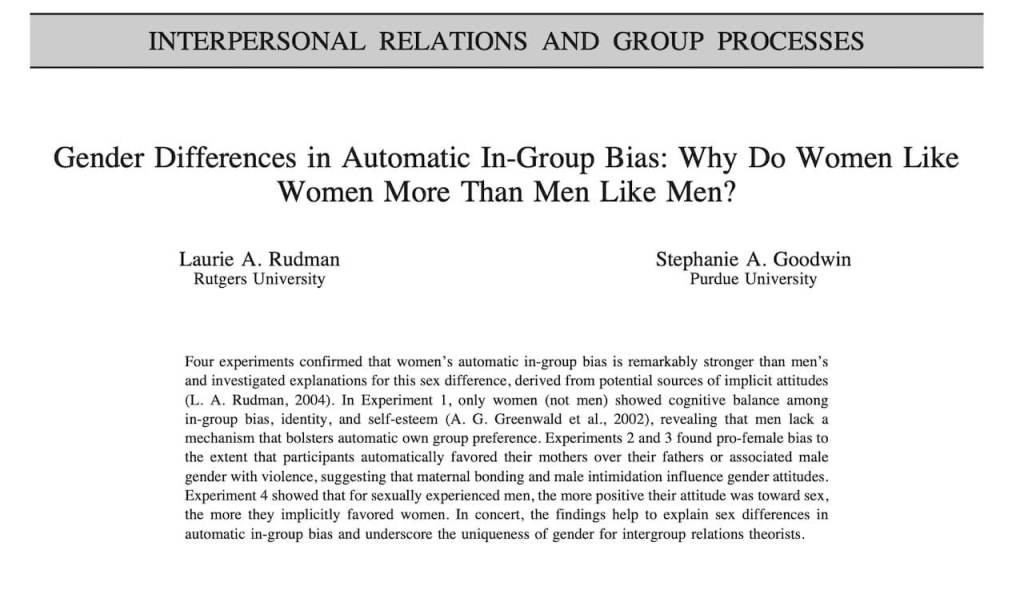

Another paper, originally published in 2004, that showed a similar bias, was recently drawn to my attention. Once again, women showed a strong (or in the words of the paper remarkable) in-group bias, but men did not. here

This study included several IAT tests albeit on smaller samples than the first paper. However, the results were consistent, both men and women, showed a pro-female bias but this was more strongly expressed in women (remarkably so in the words of the authors). The discussion part of the paper was less good. In seeking to explain the strong pro female bias they observed, it was suggested positive maternal influences and men’s stronger desire for sex played a role. There are, of course, other possible explanations. One comes from evolutionary psychology. Women are vital for the continuation of the tribe. You could drop down to a single male and the tribe would just about be viable, but a single woman would probably be insufficient to guarantee survival. For that reason, female members of the tribe could be more valued and protected and men are seen as more dispensable.

Another possible explanation is that we have come to believe that women are in some way discriminated against and at a disadvantage in society and that we must compensate for this with a pro-female bias. This, I believe, is why feminists are so reluctant to let go of their victimhood status, which brings with it immense societal power. You could view this as a form of ‘belief perseverance.’ There is ample evidence that women are not discriminated against and that society, on the whole, has a pro-female bias. In spite of this, many people, feminists in particular, cling to their belief in ‘societal misogyny’ in the face of overwhelming contrary evidence.

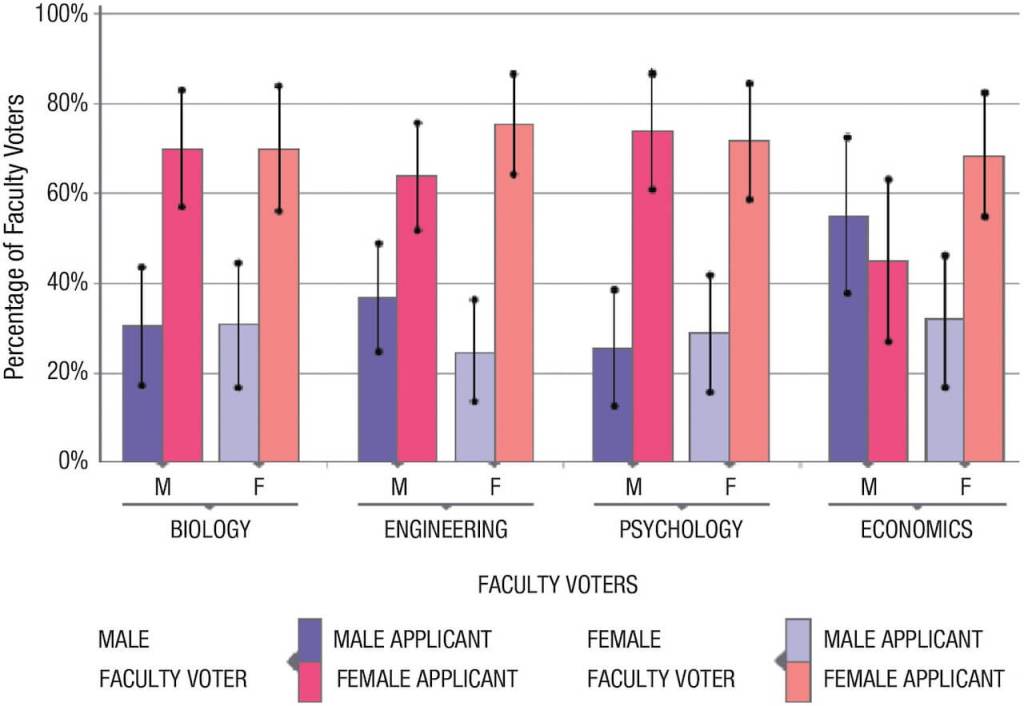

Does this matter? Or is it just the way things are and always have been? It is obviously better to see things as they are and we should be aware that the real story is one of a pro female bias, not societal misogyny. It also matters to HR departments. They need to be aware of this strong female in-group bias that tilts recruitment in favour of women and once female representation reaches a critical threshold, it can mean that departments and subject areas become ‘feminised’. There is evidence for this effect. For example, identical applications for teaching jobs are viewed less favourably if they come from men (here). Similarly, and contrary to popular mythology, studies using fake job applications show a strong pro female bias in recruitment to ‘STEM’subjects (here)

So not only do implicit bias studies show a strong pro-female bias, particularly among women, but there is evidence that this has an effect in the real world when it comes to job applications. This may be why some workplaces become feminised. Because women have much stronger in-group bias, once they reach a critical threshold in the workplace, a positive feedback loop evolves that results in their over representation.